The trees of Southern Germany were the same thin rows of pine, intermixed with low-lying grass and fern. Clearly shaped, planted, and guided by human hands. Compared to the forests of my home, with their barrel-sized fir, chaotic underbrush, and thick carpets of rain-soaked moss, something felt wrong — even dead to me. Of course, no natural environment is like the last, but what I had stumbled upon was much more symptomatic of a larger problem within the European system of forest management. An issue that, as I’ve moved to Europe permanently, only continues to bother me.

One of Europe’s most important resources and biomes might be in crisis, but how so, and how can we combat this? The answers are numerous, but I believe that to understand even a few of them, we must first look at how we got here.

A Brief History of Forestry Practices in Europe

Since the dawn of humanity, we have been shaping the natural world around us, with forests being far from an exception. Yet the rise of laws and regulations dictating how forests are to be managed is only a very recent phenomenon. In the context of Europe, it was the Romans who first introduced the idea of forests as private domains, with Germanic tribes through the 5th and 7th centuries creating an even more complex system of fines and laws. From then on, different European populations would establish their own regulations related to forest use. As an example, the English King Henry III published the “Charter of the Forest” in 1217, expanding commoners’ rights to natural resources and ending the death sentence for poaching royal game. Yet forestry, the science of forest management, would not be born until the 18th and 19th centuries.

It was then that modern-day Germany faced a crisis. After a large mining boom, many of the old-growth forests had been cleared to smelt ore, with little replanted and little remaining. Mining administrator, Hans Carl von Carlowitz, reacted to this growing crisis by compiling a guide detailing a new system of forest management and coining the term sustainability. He called for no more harvesting of timber than what the forest could naturally replenish and outlined tree farming techniques still used to this day. His work would kickstart a revolution in forestry across the continent, influenced throughout the following years by the still-new concept of sustainability, the rush of the Industrial Revolution, and the Age of Enlightenment’s desire to rationalize and conquer the natural world. This still provides the groundwork of the environmental system we have today and begs the question of whether it is time for a three-hundred-year-old system to end.

The Danger of Monocultures

The forest I first encountered in Europe, which inspired this piece, was called a monoculture, which is the result of a long-standing preference in the timber industry for hardwoods. This is in part due to their fast growth and good suitability for lumber, with an even stronger partiality going to one species in particular: Norway Spruce. These monoculture stands make up over a third of all EU forests, with over half of other forests still being limited to two or three varieties. But why should we be so concerned about this long-standing trend?

For one, monoculture stands are significantly more susceptible to the effects of climate change and less equipped to combat it. Those planted with Norway Spruce were shown to be especially affected by drought, which dominoed into increased levels of storm damage as well as insect and disease infestation. One study out of Slovakia from 2024 found that a post-drought monoculture site infected with bark beetle had a 100% mortality rate and took 18 months to reestablish soil stability. Meanwhile, its direct neighbor, a mixed species forest, was completely unaffected by the outbreak, resulting in no tree mortality.

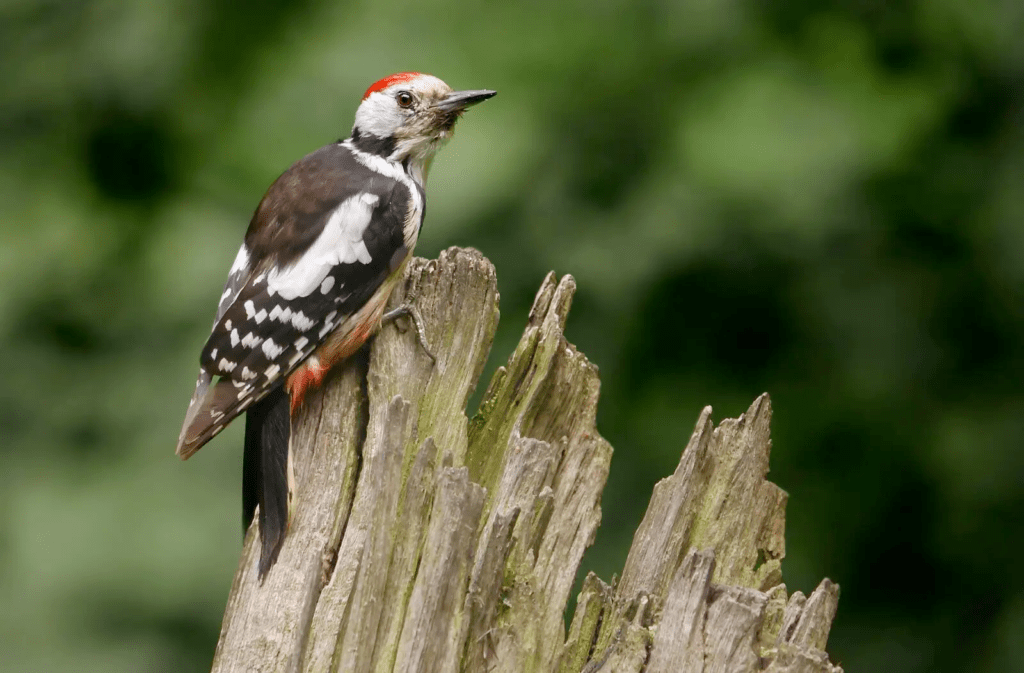

Monoculture stands in general have also been found to perform worse than mixed forests when it comes to carbon fixation and oxygen output. In a world rapidly altered by the effects of climate change, a return to mixed forests could help slow further damage. Additionally, many European wildlife species rely on mixed forest environments for survival. Birds in particular are shown to have a strong preference for more biodiverse environments, the European Woodpecker for example nests almost exclusively where multiple patches of old growth are present.

It should also be noted that an abandonment of monoculture does not mean a decrease in the wood available for harvest and human use. On the contrary, land productivity was found to increase by up to 47.3% in mixed forest alternatives. For Europe’s future, not only is the abandonment of monocultured forests better from an ecological perspective, but a financial one too.

The Importance of Deadwood

The belief that a healthy forest is a clean and tidy one often permeates many forestry-related decisions. Yet the very things seen as dangerous or dirty; fallen logs, upturned roots, rotten trees, and piles of old branches, are in reality among the most vital elements of a healthy forest.

Deadwood, as it is commonly referred to, often provides important habitats for a wide range of species. Remember those woodpeckers I mentioned? They also rely on the presence of standing dead trees, known as snags, to create nesting cavities and scavenge for insects. Amphibians and invertebrates also depend on the shelter and food that fallen logs provide, especially in periods of hibernation. One 2023 study conducted in Poland, even found that frogs and toads living in old-growth forests with high amounts of woody debris were in better body condition and twice as common as their counterparts found in forests where fallen wood was cleared.

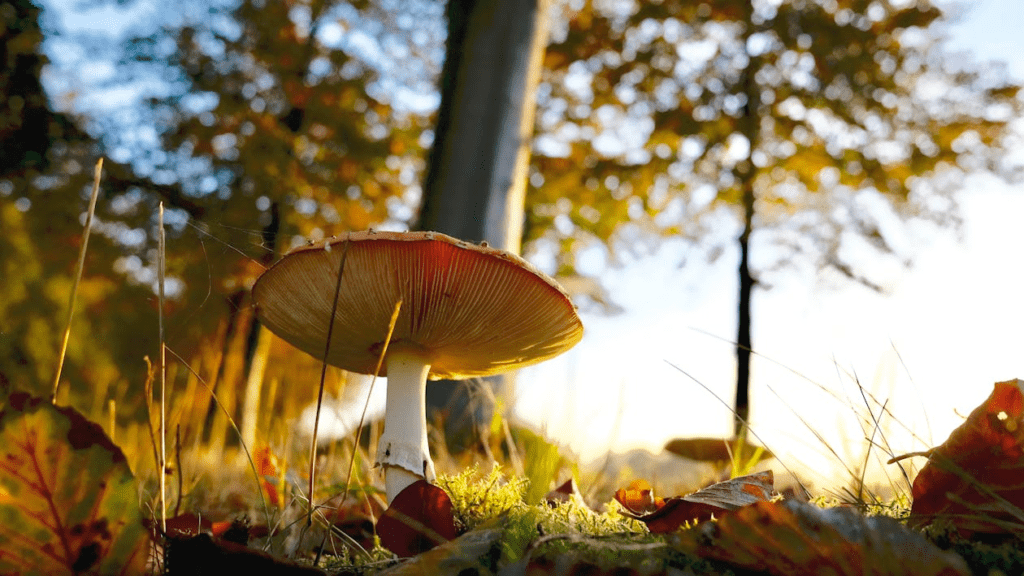

Deadwood has also been shown to promote healthy fungal and microbial communities. These both play a crucial role in the forest lifecycle, often allowing neighboring trees to grow faster and healthier, consume more nutrients, and recycle decaying foliage. Mycorrhizal fungi alone store a whopping third of all yearly carbon emissions deep within forest soil. As such, these small organisms do not just develop a healthier environment, but could prove a key player in the fight against climate change.

The Current Wildlife Imbalance

While microorganisms are certainly important, they are far from the only living things impacting forest health on such a deep level. Long ago, Europe’s numerous herbivores were managed not just by humans, but by large predators such as wolves, bears, lynxes, and even wolverines. Today, these predators have been largely reduced in number and confined to very specific regions, leaving large swathes of land to their prey. Without this natural balance and a historical downshift in hunting, deer populations have exploded in size to the point of unsustainability in many places.

One of the starkest effects of overgrazing is the decline in both quality and quantity of native flora. Deer often target fresh buds and young saplings, preventing natural growth and the replacement of trees and foliage. As an example, reports on the Thuringian forests show that over half of all trees are lost to deer before they have a chance to fully mature. This also contributes to the issue of monocultures, as often the preferred tree species are the only ones that can withstand this heavy grazing.

But it is not just trees. A Dutch study from the scientific journal Lutra, compared overpopulated and stable natural zones and found that areas with high deer populations were directly correlated to heavy decreases in native reptile, butterfly, bee, and bird populations. Ground-dwelling species are especially affected not just by the decrease in habitat and available food, but also by trampling.

This issue is unfortunately not as easy to solve as planting more diverse tree species or letting dead wood rot either. While some have proposed a reintroduction of native predators as a key step in restoring Europe’s natural ecosystem, many, particularly farmers and politicians, meet such an idea with criticism. Europe is more densely populated with less natural space than in the past, raising the potential of dangerous human and livestock interactions.

Meanwhile, initiatives promoting the hunting and culling of deer have also garnered controversy due to ethical concerns. Yet a study from the University of Freiburg showed that even in environments with carnivores, natural predation was largely ineffective at reducing population compared to human intervention. It is a complicated and multifaceted problem, but at its core, one issue remains. There are far too many deer for a sustainable forest ecosystem.

The Future of European Forestry

While these issues are still present in forests across the continent, the EU and national governments have taken several steps to address them. As one example, the EU Forest Strategy for 2030, passed in 2021, aims to directly improve the quality and quantity of European forests. Initiatives include the protection of current old growth, increases in biodiversity and forest size, restoration of native ecosystems, and financial incentives for forest owners and managers.

Public mentality has also shifted entirely from the early days of sustainability and its founder, Hans Carl von Carlowitz. Modern society is far more cognizant and educated on the importance of a healthy environment, and cares more about the ecological impact of its industries. I have faith that while Europe’s forests are certainly struggling and not as healthy as they could be, its passionate citizenry will be the first to push development. So yes, while Europe’s forests are in crisis, the future is wonderfully bright.