Cover photo: Laura Lövei, Hallgató Magazin

THE ANTIQUITY

Going back to the ancient Greek festivals, – to the roots of Western Theatre – records are to be found of the Eleusinian Mysteries being suffused with a great variety of aromas: flowers, fruits, oils, wine, honey, the burning of animal flesh and incense. Accounts of the integration of scent into dramatic performances can also be detected in the descriptions about the resourcefulness of the design of Greek plays by writers such as Ovid and Apuleius. For instance, one of these mentions a fine saffron mist sprayed over the audience.

THE MEDIEVAL AND THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD

As the appeal of pageant wagons grew but the frequency of hygienic practices did not, it is highly probable that there was already an unintended olfactory backdrop to performances – and a rather malodorous one at that. The stench of crowds could not be better illustrated than by the fact that some accounts mention rosewater fumigations being used upon the arrival of Edward IV’s wife, Elizabeth of Woodville in London to protect her from the unwanted stink.

To top this olfactory backdrop, smell-emitting practices were carried out on the stages as well. For example, the stage directions in Macbeth calling for thunder and lightning would have been produced by means of squibs and small fireworks, which would fill the air with the smell of gunpowder. According to scholars, Shakespeare’s audience was likely to connect this sulphurous smell not only to the event taking place on stage, but also to the recent political events in England, as the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was uncovered in the months preceding Macbeth’s first performance in 1606. This speculation underlines the multiple roles of smell: setting the tone and mood, triggering memories, and serving a narrative end as well by adding more layers of interpretation to the performance.

THE LATE MODERN ERA

Speaking of tone and mood, Oscar Wilde planned to use a whole set of mood-enhancing fragrances during his play entitled Salome. Instead of an orchestra, his vision was braziers of perfume: “Think – the scented clouds rising and partly veiling the stage from time to time – a new perfume for each emotion.” Had it not been for the technical limitations, it would have been a sensational performance, but there was no way to effectively air the theatre between the distinctive emotions.

However, as a result of technological advancements and accessibility to perfume, almost Wilde-like designs of fragrance use became possible both on stage and in theatre halls. An illustrative example of such is the opening of The Gaiety Theatre in London in 1868, for which scent fountains in the lobbies and scented programme fans were provided by the London-based perfumer Eugène Rimmel – an ingenious way to market his wares.

A play entitled A Trip to Japan in Sixteen Minutes by Carl Sadakichi Hartmann, presented at the New York Theatre in 1902, incorporated the sequential release of a series of 8 scents. Hartmann’s intention was to evoke the different stages of the journey by means of scents associated with the specific location: almond for Southern France, bergamot for Italy, cedarwood for India, carnation for Japan and so on. However, reports indicated that the audience’s associations tended to be rather unpredictable. This could have been partly due to the problems with the release and especially the clearance of the scents, but it also underlines the elusive nature of fragrance and the importance of personal experiences connected to detecting a scent.

TODAY’S CONTEXT

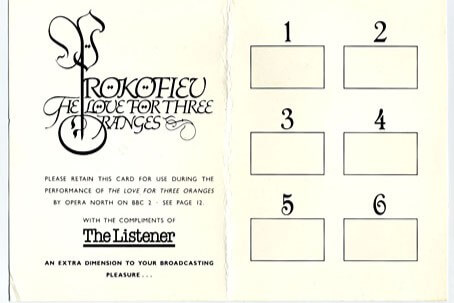

An inclination for a more experimental approach to the staging of smell was demonstrated by Richard Jones, who directed Prokofiev’s opera called The Love For Three Oranges for the National English Opera in 1989. It was broadcast on television by BBC, whose weekly magazine, The Listener previously distributed scratch-and-sniff cards created by Givenchy for viewers to use at home. There was an altogether number of 6 scents to be scratched at different parts of the performance. In this case scent became a theatrical object, almost a character itself and the audience was responsible for the outcome of the multisensory experience.

A more drastic approach to scent integration into performances was showcased at the Future of StoryTelling conference, held annually in New York. A couple of Dutch scientists/artists aimed at reconstructing the last moments of famous people, whose deaths are ingrained in our collective recollection (for example Princess Diana, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, and Whitney Houston) – with the use of scents and sounds. Members of the audience could choose whose death they wished to ‘be part of’, after which they were instructed to lie down on a metal tray and were rolled into a pitch dark mortuary fridge.

However bizarre this sentence may sound, Charles Spencer experimental psychologist at the University of Oxford opted for the death of Whitney. He gave a detailed account of his experience:

“The dominant visual sense having been effectively eliminated, I got to experience the preprogrammed sequence of sounds and associated scents. These included the sounds of splashing water and Houston’s voice; I first caught a whiff of generic hotel cleaner, followed by the olive oil that the singer used in her tub. Then, a strong chemical odour, similar to that of cocaine, fills the box, grabbing its occupant by the throat, followed by the sound of rushing water, the electric crackling of her hairdryer short-circuiting as it slipped into the water, and finally silence.”

No matter whether the use of scent is deliberate, incidental (the smell of actors smoking on stage), orienting or maybe disorienting (the smell of flowers at the butcher’s), it always serves one end at least: connection. Awareness on the audience’s part that they inhale the same scent-suffused air as the actors, the sharing of the same olfactory experience helps to integrate the spectators into the action. Fragrance, therefore, has an immense psychological influence – it makes the audience realise that they are being invited into the intimate spheres of the actors, and thus their bond is strengthened.