Cover image: criterion.com

From Shakespeare’s London to the opera houses of Beijing, from royal courts to private gatherings in Afghanistan, femininity has been carried by those born outside it. These performances — delicate, precise, often heartbreaking — reveal something about societies that silenced women yet longed for their reflection.

In Elizabethan England, the theater celebrated imagination but built its walls around it. Women were banned from performing, their presence thought to threaten morality and social order. The stage was a man’s world, and in that world, boys stepped into womanhood. They played the tender lovers, the grieving queens, the betrayed wives speaking lines written by men who imagined what women would say if they could speak.

The illusion was powerful enough to move entire crowds. The audience laughed, wept, and believed. A boy’s unsteady voice, caught between childhood and adulthood, carried an innocence that made tragedy feel pure. Edward Kynaston, one of the last of these “boy players,” became famous for his portrayals of female characters before women were finally allowed on stage after the Restoration. His performance as Desdemona was said to bring audiences to tears. But when women entered the stage, the art that had defined him disappeared overnight. What was once admired as talent became unnatural.

Centuries later, and a continent away, the same paradox took a different form in China. In Peking Opera, the dan, male performers who specialized in female roles, became the heart of the art form. Their movements were so graceful, their gestures so deliberate, that audiences forgot they were watching men. Every flutter of a sleeve, every measured glance, carried the weight of years of training.

One of the Greatest Chinese movies of all time that still shapes the art of cinema, Farewell My Concubine, clearly depicts this faith of the male performers who were given the task of sculpting women by their own existence. In the movie, the second male lead becomes so immersed in his role that he cannot separate himself from it. “I am by nature a girl,” he says at one point, and it feels less like a line from a play than a confession. His art gives him power, but it also consumes him just as it consumed so many who came before.

Among such performers, Mei Lanfang became a legend. Born in 1894, he began performing at the age of ten and went on to redefine the role of the dan. His portrayals of tragic heroines and elegant concubines brought him international fame. When he toured the West in the 1930s, audiences were captivated. Charlie Chaplin called him „artist of the highest order”, Bertolt Brecht said that watching Mei Lanfang perform changed his understanding of theater.

For Mei, playing a woman was not a disguise but devotion. He studied how women walked, spoke, and held emotions. Some people say he was born for this role since his father was also a prominent dan player himself. His aim was not to imitate but to embody an ideal, to create a vision of womanhood that existed somewhere between truth and art. Yet the paradox remained. While Mei was celebrated across the world, real women were still absent from the stage. Their silence continued, refined and aestheticized, performed through men who had learned how to be them.

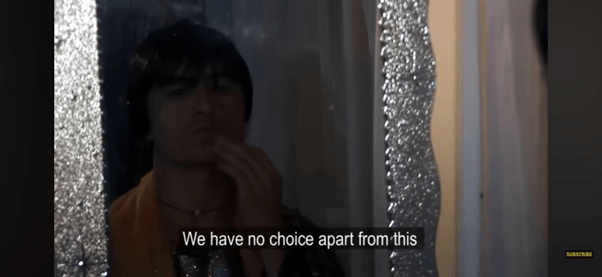

That same mixture of beauty and absence appears again in a much harsher setting. In Afghanistan, the tradition known as bacha bazi, “boy play”— literal translation in English, carries none of the theater’s protective distance. It takes place not on stage, but in secret gatherings, where young boys dance for men who forbid their mothers and sisters from appearing in public. The practice dates back centuries, to a time when female performers were banned.

What began as a substitution gradually turned into a far more complex and painful ritual that exposes power, desire, and control. The boys, often from poor families, are chosen for their looks, dressed in women’s clothes, and taught to dance. Music fills the room, but the air is heavy. The audience claps; the boys keep moving. For many of them, the dance is not a performance; it is survival.

There is no applause when it ends. The beauty of their movement is inseparable from its cost. Anthropologists describe batcha bazi as a reflection of a deeply gender-segregated society, where even the imitation of womanhood must come from men. In these moments, femininity is both desired and denied, celebrated and punished.

A strange thread connects these stories from London’s candlelit theaters, through Beijing’s painted stages, to the hidden courtyards of Central Asia. Each boy steps into the role of a woman not because he chooses to, but because the world around him has left no space for her. Each performance becomes a portrait of absence, of longing for something that society itself has erased.

Art often emerges from restriction, and these performances are proof of that. But they are also reminders of the quiet cruelty behind beauty and how art can preserve what the world forbids, yet never replace it. The boy in the mirror, centuries away, might not know their names. But he stands in their shadow. His reflection belongs to a long, unbroken history of those who performed femininity when real women could not. Each movement he rehearses carries the memory of others who did the same, not in freedom, but in the space left by absence.

Performance, in the end, is a kind of remembering. Every trace of powder, every soft movement, is a way of holding on to something lost. And when the curtain falls, whether in a London playhouse, a Beijing theater, or a dim Afghan courtyard, what remains is not the illusion but the question it leaves behind: why was it ever needed?