Grey Dead Zones: Parking Lots

Parking lots are one of the greatest sins of modern cities, a consequence of the revolution of the automobile that followed World War II. Surface-level parking lots occupy incredible amounts of space while offering little, either from a humanitarian or in an economic aspect. Budapest, along with some other Hungarian towns and cities are generally successful at not creating surface parking lots, or at least reducing their sizes, especially within the city centre.

When it comes to parking lots, Budapest has done a great job cleaning up these dead spaces in the city. In 2014, Budapest successfully renovated Kossuth Square, transforming the parking lot it was before into a public park that both the citizens of Budapest and tourists can now freely enjoy.

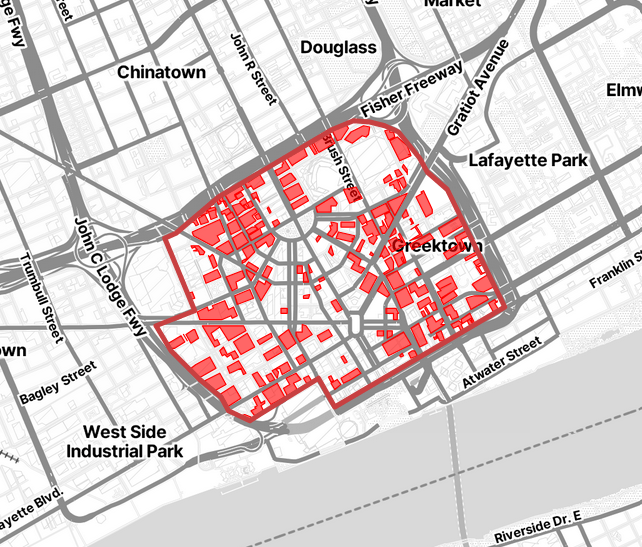

American cities, on the other hand, have not performed as well as Budapest has in this regard. The United States, the birthplace of the automobile, has allowed many, if not all of its cities to be dominated by the car and the requirement of building parking lots. Cities like Detroit, the cradle of the automotive industry, have dedicated 31% of their city center to surface-level parking lots. This is a devastating statistic for any city. Not only does it create a barrier within the city socially, but it also impacts the economy.

How can surface-level parking lots affect cities on a human level? The most important aspect of a city is how its residents exist within it on a daily basis. Ideally, as a person walks along the streets, they should be greeted by façades of buildings and be able to enter their destination simply right off the street, not by walking an extra few minutes dodging cars in a parking lot. In simpler terms, a city without parking lots is often more visually appealing and attracts more people than one dominated by grey seas in front of every building.

The economic perspective also shows that surface-level parking lots do more harm to the economy of a city than what they provide in return. First, let’s begin with the most damaging type: free surface parking lots. Now, are these parking lots actually free? Absolutely not. This is the first problem with these parking lots. Everyone ends up paying for them, whether they use them or not. While they aren’t paid through imposed taxes, the costs are hidden within everything else. No matter where you go, you end up paying a small but real price for the “free” parking, whether you arrive by walking, bus, tram, or any other mode of transportation.

If you’re shopping at a grocery store, a fraction of the price you pay for each can of Coca-Cola and apple will be used to cover the maintenance and cleaning of the parking lot. The prices might not be noticeably higher, but your purchases at these places do contribute to the cost of those vast expanses of grey whether you like it or not. This issue is mainly present in the United States. Luckily, in European cities such as Budapest, you’ll be hard-pressed to find any sort of parking in the centre surface level or not, which doesn’t charge a fee. However, on the outskirts of towns, at large supermarkets such as Tesco and Auchan, you’ll still find parking lots where the same system is in place as in America

That is the core problem with free parking lots. Of course, there is still a problem with the vast grey lakes within cities, regardless of whether they charge a fee at the entrance. They take up too much space that could be used for more valuable purposes, such as housing, shops, and other spaces where people spend far more time than in a parking lot. When it comes to housing, which is one of the most important aspects of a city for its residents, the impact can be quite catastrophic.

Parking lots built for apartment buildings, or in general, reduce density. The late Donald Shoup, in his book The High Cost of Free Parking, found that if a building required 1 parking space per apartment, population density would be decreased by 31% and land value would decrease by 33%. These take up space that could otherwise be used for more housing, allowing more people to live in a given area and increasing the overall housing supply, which people are in dire need of in cities all around the world.

Green Dead Zones: Empty Lands

By “green dead zones”, I don’t mean parks (which are vital parts of cities) but rather abandoned industrial areas often overgrown with grass, giving them the false appearance of being green, especially from above. These zones shouldn’t be left untouched. Cities that contain them should actively work to redevelop them into areas where people can properly live. Often, these zones are in prime locations for redevelopment and would be attractive for future residents.

One such space in Budapest has recently been in the news due to a debate between the capital city and the Hungarian government over what should be built there. The project was originally proposed by Arab property developer Eagle Hills (whom I’ll mention again later) and gained significant attention in the Hungarian media in late 2024. The plan quickly became quite unpopular, mostly because it featured incredibly tall Dubai-style skyscrapers close to the city centre. It didn’t take long for the public to negatively nickname the project “Mini-Dubaj”. The mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony responded with his own “human-scale” plan, designed to better align with the city’s urban fabric and would be more liveable and people-friendly on a wider scale. Luckily for Budapest, the plan of “Mini-Dubaj” has been scrapped, as the city purchased the land originally designated for the project with the intention of building their own human-scale development.

It is important that development projects, when getting rid of these dead zones, whether green or grey, should still respect the culture and the urban fabric of the city, and shouldn’t be less liveable despite the redevelopment of a dead zone. The Serbian capital, Belgrade, was less fortunate in this regard.

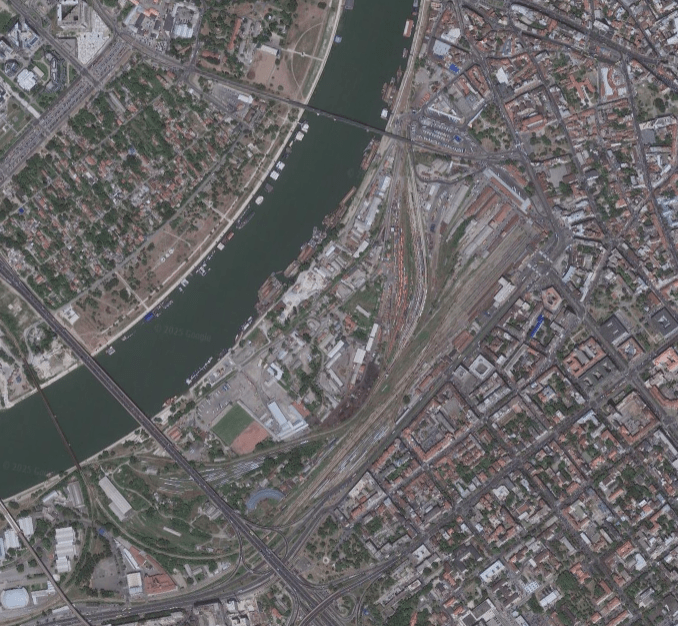

In 2014, Eagle Hills was selected by the Serbian government to redevelop the dead zone surrounding the main train station and the Sava River. The project, Beograd Na Vodi, was considered to be very shady from the start due to the suspiciously non-competitive process through which it was awarded. The goal was to redevelop the largely abandoned area around the train station, including the station itself. Fast forward to today, the project is nearing completion. However, Serbia and Belgrade no longer have a main train station, as the project removed the tracks and built modern apartment blocks over its bones. These apartments are unaffordable for the majority of Serbs, and stain both the skyline and the urban environment of the city.

Redeveloping these dead zones within cities is essential for both economic and human benefit. However, it’s equally important to ensure that these developments do not come at the expense of the city. They should be designed to fit the environment of the city, so it can become a better place for everyone. Not just building a casket on its already dead zones.