Background photo: image.tmdb.org

Today, however, we will explore the topic through the example of another classic. Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell became a bestseller upon its publication in 1936 and gained even greater popularity with the release of the film three years later. It was not only one of the longest films ever made, but it remains the most profitable film of all time (adjusted for inflation). It earned its creators ten Oscars and contributed to the popularisation of colour cinema. Surely, these achievements are hard to surpass by any new adaptation, but should we at least try?

Why Is It Even Necessary?

When discussing the remake of a classic adaptation released decades ago, we need to understand that age truly makes a difference. Gone with the Wind was filmed nearly ninety years ago, in another historical era, when both Hollywood and technology were drastically different. While the length of the film is undoubtedly impressive, in terms of the screenplay it is not as close to the original as it could have been.

One of the main reasons for this lies in the lack of resources. The book accumulates an abundance of storylines and characters in order to illustrate its central idea — the collapse of one civilisation and the birth of a new one. Surely, it is impossible to include every aspect of such a plot in a single film, even if it is four hours long.

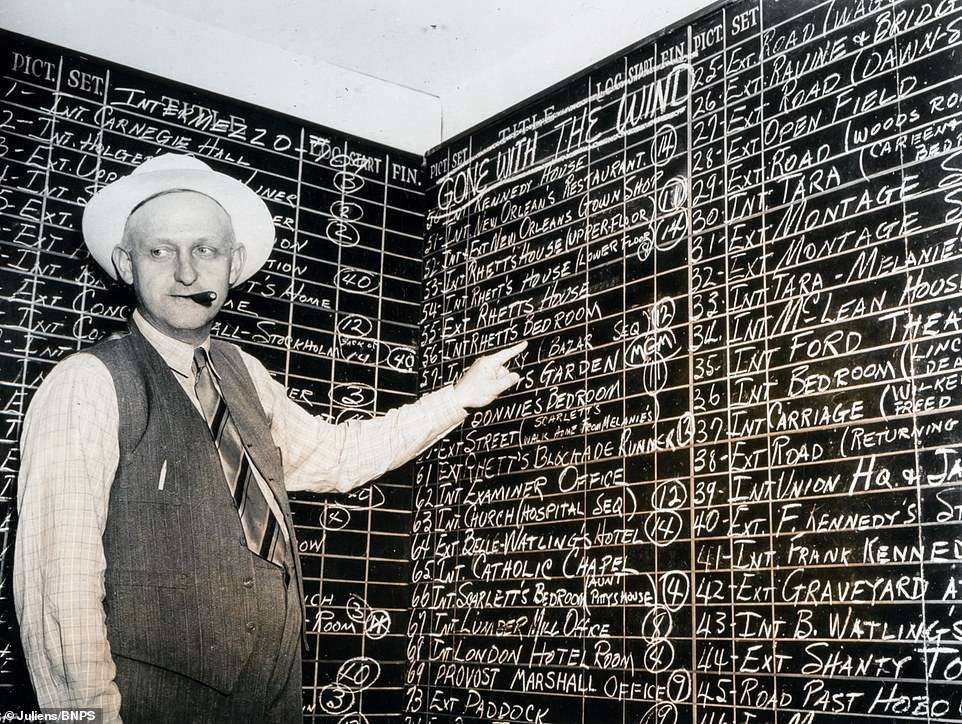

However, it perfectly fits into the format that 1930s Hollywood lacked and that modern audiences enjoy even more than films themselves — Gone with the Wind could easily be adapted into a television series! Additionally, today’s film industry certainly possesses far greater budgets and more advanced technology than that available to David O. Selznick, allowing the depiction of the Civil War and pivotal scenes such as the fall of Atlanta in vivid detail.

Source: dailymail.co.uk

Another reason why the screenplay altered so much of the dialogue in the key scenes has to do with the nature of 1930s Hollywood. The Motion Picture Production Code, widely known as Hays Code, was a set of rules implemented in 1934 to keep the film industry “moral” and to avoid government censorship. It strictly prohibited any suggestion on “inappropriate” topics such as violence or intimacy (including, for instance, the rule of “no passionate kissing for more than three seconds!”), forcing directors to change not only the depiction of war but also the characters’ stories and dynamics.

The relationship between Rhett and Scarlett suffered the most, as with the removal of “sensitive” topics much of their original emotional depth, complexity and passion was gone — with the wind! Fortunately, in modern Hollywood, the Hays Code has been replaced by a rating system, allowing filmmakers to explore a far wider range of themes without fear of internal censorship

Lastly, Gone with the Wind was, like many old films, simply a product of its time. Made during the era of Jim Crow laws, it did not attempt to challenge the racist viewpoints depicted in the original novel but rather reinforced this narrative. This can clearly be seen in the further simplification of the African American characters, the use of racial slurs, and the inclusion of intertitles that highlighted the Southern “Lost Cause” ideology, describing the plantation era as “pretty world, where Gallantry took its last bow” (Gone with the Wind, 1939).

Today, both the novel and the film are rightly subject to fierce criticism for these views. This is exactly where a new adaptation could learn from past mistakes and comment on both the characters’ and the author’s perspectives rather than validating them.

But Is It Still Relevant?

While we have illustrated that there are many reasons for filmmakers to remake old films, the elephant in the room must be addressed. Are these stories still as relevant to a modern viewer as they were back in the day? There is, of course, no universal answer. Some plots work just as well today as when they were first released, while others targeted a specific audience and therefore require careful reshaping to feel engaging again. Yet, when it comes to the classics, the situation is not as grim as it might seem at first glance.

Classical literature is so widely praised precisely because it appeals to timeless, universal themes that remain relevant regardless of the era. Gone with the Wind touches on topics of wide taste: war and loss, unrequited love, defying society, fighting for what is yours, and building one’s identity, etc. These were important during the time of the Great Depression and are still easy for a viewer to relate to today. Combined with a potentially extended runtime, a new adaptation could become just as — if not more — captivating for a modern audience as the 1939 version.

Speaking of Gone with the Wind’s relevance specifically, the story also fits within an active trend in modern literature — the dark romance. The Hays Code resulted in the simplification of both the main characters and their dynamic, but the book-accurate Rhett Butler is precisely the type of character that dark romance authors strive to create. Morally grey, sarcastic, intelligent, and powerful, he nevertheless loves Scarlett deeply and waits years for her to love him back. She is not much better than he is, equally strong-willed, stubborn, and unwilling to follow anyone’s lead.

Together, these two serve as an example of a difficult yet passionate relationship filled with yearning, one that could easily surpass nearly any fictional couple in the genre today and bring the adaptation even greater success. Provided it is depicted in a correct and nuanced way, of course.

Bringing classical literature to the screen was never an easy task in the first place, and the existence of successful adaptations only makes it more challenging for directors. However, as experience shows, it is never a “lost cause” as long as the creators approach the material with a unique vision and respect for the original. In that case, the new version has every chance not only to equal, but even to surpass the old ones. War and Peace, Pride and Prejudice and Little Women are already there, Wuthering Heights is on its way, so perhaps Gone with the Wind also stands a chance?