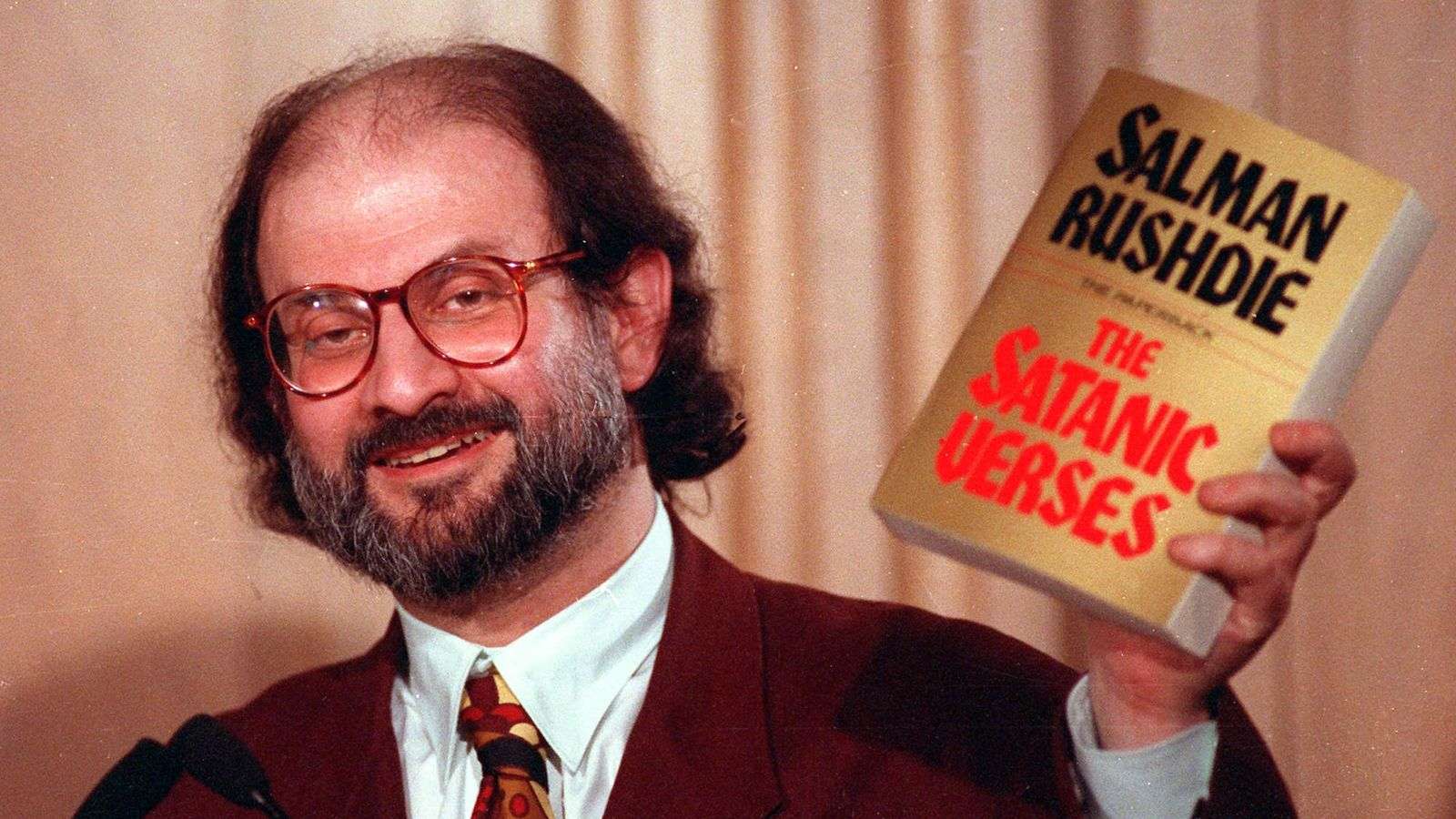

Cover photo: Author Salman Rushdie with his controversial novel. Source: news.sky

Salman Rushdie – The Satanic Verses (1988)

In February 1989, Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini publicly condemned Indian-born British writer Salman Rushdie and issued a fatwa calling for the author’s assassination. This was provoked by Rushdie’s work entitled The Satanic Verses, a magic realist novel about two Indian Muslims living in England, which — although fictional — Khomeini deemed highly blasphemous, depicting prophet Muhammad immoral and using his wife’s names for prostitutes. Muslims were so offended that a radical organization, the 15 Khordad Foundation even went as far as to offer a bounty to the one who would murder Rushdie.

Consequently, Rushdie spent almost ten years of his life hiding, but continued to write and publish despite the death threat. Finally, in 1998, the government of Iran declared that it would cease enforcing the pronouncement against the author. Rushdie then moved to New York and returned to public life. In 2022, more than three decades after the issue of the fatwa, Salman Rushdie was severely attacked at a literary event in Chautauqua, New York, while onstage to give a speech on the US being a refuge for exiled artists. The attacker was the 24-year-old Hadi Matar, who was not even born at the time of the decree of the fatwa. Rushdie was stabbed fifteen times, suffered permanent injuries, and was left partially blinded.

However, it was not only Rushdie the fatwa targeted, as it also incited the assassination of anyone “aware of [the book’s] contents.” As a consequence, Hitoshi Igarashi, the novel’s Japanese translator was found stabbed to death in his office in Tokyo in 1991; Italian translator Ettore Capriolo was attacked similarly in Milan the same year, but survived, and so did William Nygaard, the publisher of the Norwegian translation, shot three times outside his home in Holmenkollen in 1993.

Roberto Saviano – Gomorrah: Italy’s Other Mafia (2006)

“For a lot of people, writing is just a job you do, there are no consequences. But for others, it’s not like that,” — claims Italian writer, journalist, and screenwriter Roberto Saviano, who managed to uncover the Neapolitan mafia through his book of investigative journalism, and his life has not been the same since. Although the Savastano clan around whom the book revolves is fictional, Saviano uncovered the real-life Casalesi clan by providing insight into its organizational structure and businesses.

The book was the result of serious undercover work, as Saviano infiltrated the Neapolitan Camorra, the organized crime syndicate to which the Casalesi clan belongs. He managed to acquire many roles within the organization, ranging from an assistant at a Chinese textile manufacturer, through a waiter at a mafia wedding, to working on a mob-run construction site. By bringing his expertise to the public sphere, Saviano added immense public attention to the maxi-trial referred to as Spartacus, already underway since 1998. Two years after the book’s publication, a pivotal verdict was finally announced: 27 life sentences, including that of Francesco Bidognetti, leader of the Casalesi.

Saviano had been receiving threats even before the Spartacus verdict was born; however, he was publicly declared the target of the mafia in March 2008 when the lawyer of two bosses read aloud a document claiming that he and Rosaria Capacchione, another journalist reporting on the mob, would be blamed if the defendants were found guilty. After the death sentences, the situation escalated quite quickly, and Saviano had to keep a low profile, getting around only if followed by bodyguards and bulletproof cars. No spontaneity was allowed, his days were planned minute by minute, which left him in some sort of a limbo: neither fully alive nor yet dead.

Finally, after 17 years, justice was done, as on 17 June 2025, the Rome court of appeals confirmed the 2021 ruling by a lower court, which found Bidognetti and his former lawyer, Michele Santonastaso, guilty of mafia-related threats against Saviano. Prior to this, when asked about regretting writing Gomorrah, Saviano would usually reply “As a man, yes, as a writer, no,” but then he goes on to add

“For most of my waking hours I hate Gomorrah. I loathe it. […] I miss the time I was a free man. Whatever I would like my life to be, the fact is, I wrote Gomorrah, and I pay the price every day.”

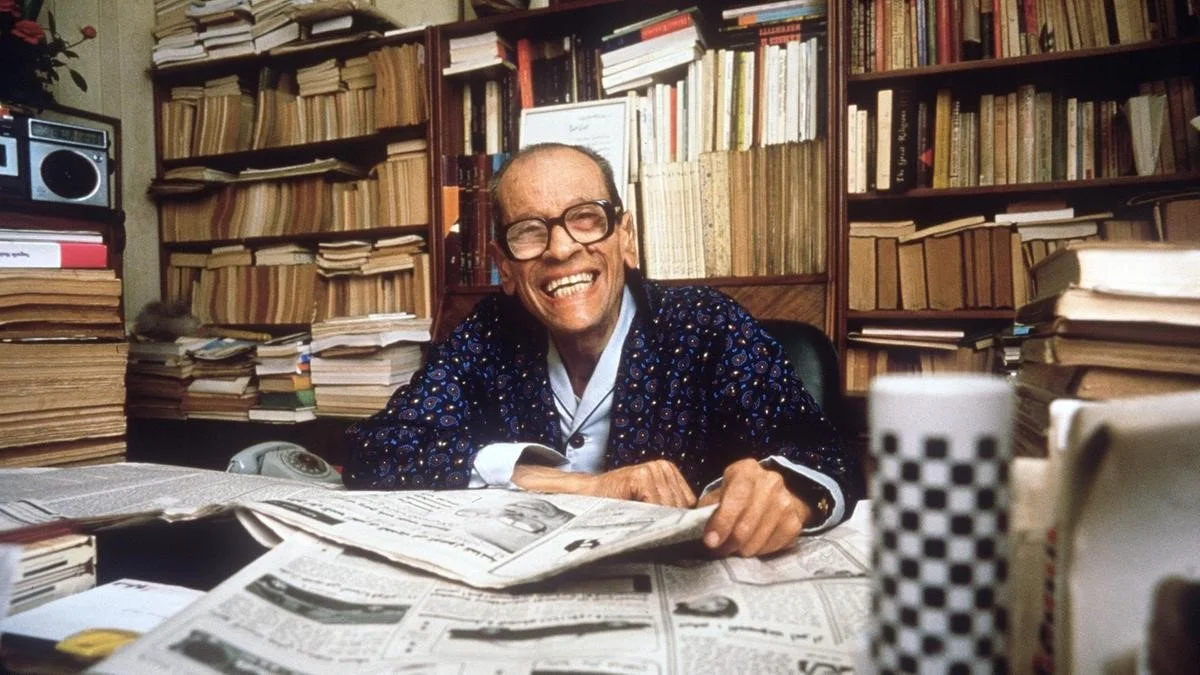

Naguib Mahfouz – Children of the Alley (1959)

Similarly to Salman Rushdie, Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz was also the target of a fatwa by cleric and later convicted terrorist Omar Abdel Rahman on account of deeming Mahfouz’s novel Children of the Alley sacrilegious. The novel follows a neighbourhood in Cairo through successive generations, becoming an allegory for the central narratives of the Abrahamic faiths — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The main fictional figures are mapped onto the three prophets (Moses, Jesus, Muhammad), while a fourth character, Arafa, stands for modern science.

Religious critics targeted the author for presenting the holy figures as secular, flawed human beings and for suggesting that knowledge (Arafa) could contribute to human life in ways that religion has failed to. As a result of the immense backlash, Children of the Alley was banned in Egypt for several years and could only be republished after the death of Naguib Mahfouz in 2006. Although the author clearly considered his novel to be symbolic fiction, possible to be interpreted in a plethora of ways, he remained the target of religious outrage.

Despite the controversies, Mahfouz did not give up writing and became the first Arabic-language author to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988. However, international acclaim did not stop religious groups from feeling offended, and eerily echoing what happened to Rushdie 28 years later, in 1994, an extremist stabbed Mahfouz in the neck outside his Cairo home, leaving him seriously injured and partially paralyzed.

All three accounts have triggered worldwide debates about the freedom of expression and artistic license. These authors proved that writing, fictional or not, carries weight and shapes reality. As Margaret Atwood — who was likewise the target of threats regarding The Handmaid’s Tale — put it:

“Words are our earliest human technology, like water they appear insubstantial, but like water they can generate tremendous power.”